For my Summer Project I decided to research the beginnings of Visual Journalism and the career of it’s pioneer Robert Weaver.

Reportage, as Visual Journalism is also known, is defined as ‘a technique of drawing that tells a story entirely through pictures to give an account of directly observed or researched events’ – essentially the artist taking the role of the journalist. Visual Journalism became extremely popular during the mid-fifties and 60s as the popularity of ‘Rockwellian’ illustration – the typical editorial style during the early 20th century – declined. As such, Reportage became a staple of every established American publication from ‘LIFE’ to ‘Sports Illustrated’ to ‘Playboy’ to ‘Cosmo’ during this period.

The realistic styles of Al Parker and Norman Rockwell that were popular in the early 20th century fell into decline in the post-war period. Often based on models and photographs, their work presented an idealised image of American life as opposed to the gritty reality showcased by the work of Visual Journalists such as Robert Weaver.

The realistic styles of Al Parker and Norman Rockwell that were popular in the early 20th century fell into decline in the post-war period. Often based on models and photographs, their work presented an idealised image of American life as opposed to the gritty reality showcased by the work of Visual Journalists such as Robert Weaver.

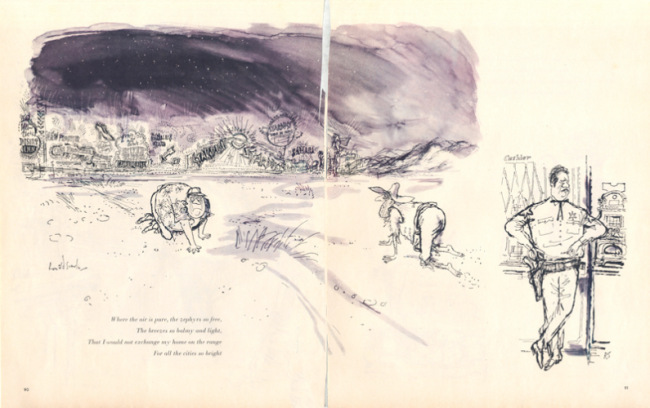

As Reportage began to flourish, magazines would constantly be sending it’s artists out into the field to capture the subject matter of editorials as it happened, an entirely new concept that allowed the artist to create an image much more true to life than any based on a photo or models drawn in the security of a studio.

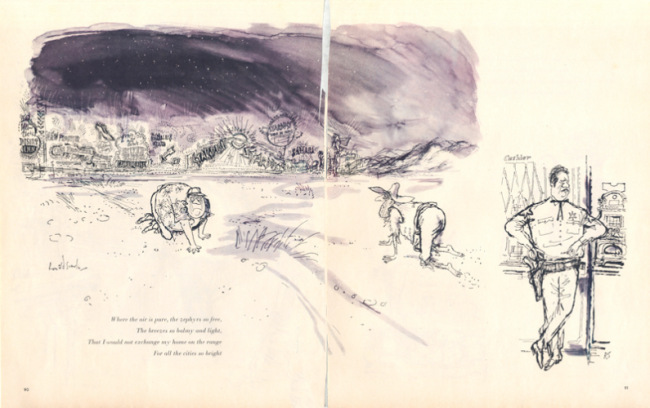

Robert Searle for ‘Holiday’ magazine, which would send him to a variety of locations throughout North America and Europe to document his travels through illustration and text – often expecting him to cover up to 20 pages with full colour images.

Robert Searle for ‘Holiday’ magazine, which would send him to a variety of locations throughout North America and Europe to document his travels through illustration and text – often expecting him to cover up to 20 pages with full colour images.

During the 50s and 60s it became common to see illustrations depicting the gritty aspects of current culture: race, crime, sports, war and poverty. This allowed for a new breed of immersive, involved and lively editorial art the likes of which never seen before.

This golden era of Visual Journalism was pioneered by Robert Weaver, and illustrator considered the ‘father’ of Reportage.

Unlike their predecessors, Weaver and his contemporaries were more interested in drawing scenes from life – as seen in his sketches above.

Unlike their predecessors, Weaver and his contemporaries were more interested in drawing scenes from life – as seen in his sketches above.

Robert Weaver was born in 1924 Pittsburgh. His artistic education included a variety of establishments: The Carnegie Institute of Technology, New York’s Art Students League and Le Academia Delle Belle Arti. A brilliant draftsman with a drawing style reminiscent of Ben Shahn and Austin Briggs, he was part of a new breed of illustrators being influenced by the impressionism and expressionism art movements of the 1950s.

Another influence in both Weaver’s life and the Visual Journalism movement as a whole was Leo Lionni, a dutch illustrator and author. Lionni relocated to America in 1939 and from there out spent the next 23 years as an art director for several advertising firms as well as at ‘Fortune’ Magazine. Under Lionni, artists were tasked with ‘[doing] the things they weren’t accustomed too’ and under his encouragement Weaver was pushed to ‘break the rules‘ of traditional illustration .

Robert Weaver for ‘Fortune’ magazine, an extract of an editorial on the work of Crane Co. Harmonious use of colour with rough and dry application.

Robert Weaver for ‘Fortune’ magazine, an extract of an editorial on the work of Crane Co. Harmonious use of colour with rough and dry application.

It was during his time at ‘Fortune’, Lionni and Weaver became involved with one another. Weaver would later say that ‘Lionni trusted the artist, and once he picked the right practitioner, he left him alone.’ and of ‘Fortune’ magazine Weaver add: ‘That was Fortune’s policy, to send artists on stories. I was sent to Ohio and Alabama, just all over. Sports Illustrated later did the same thing’.

Roberta Smith of ‘The New York Times’ described Weaver’s style as: ‘[the combination of] loose, rough-hewn rendering, deft abbreviations and sometimes elements of collage, with a startling degree of realism that seemed to capture of essence of any face or pose without resorting to photographic detail.’

This, I feel, sums up my attraction to Weaver’s work. While photo-realistic art is undeniably impressive, there’s something wholly more attractive to me about taking a scene or character and making it recognisably ‘yours’. It is this lack of photographic detail that first drew me to Weaver’s work. I found his impatient, expressive and abstracted style with daring and confident use of line work fascinating – being someone who gets nervous drawing with something as permanent a ball-point pen!

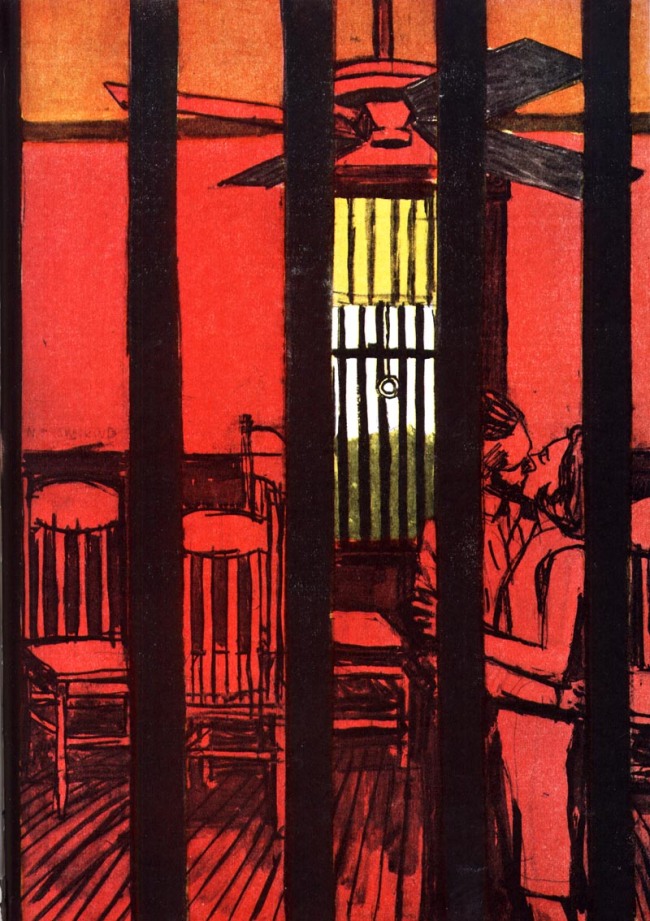

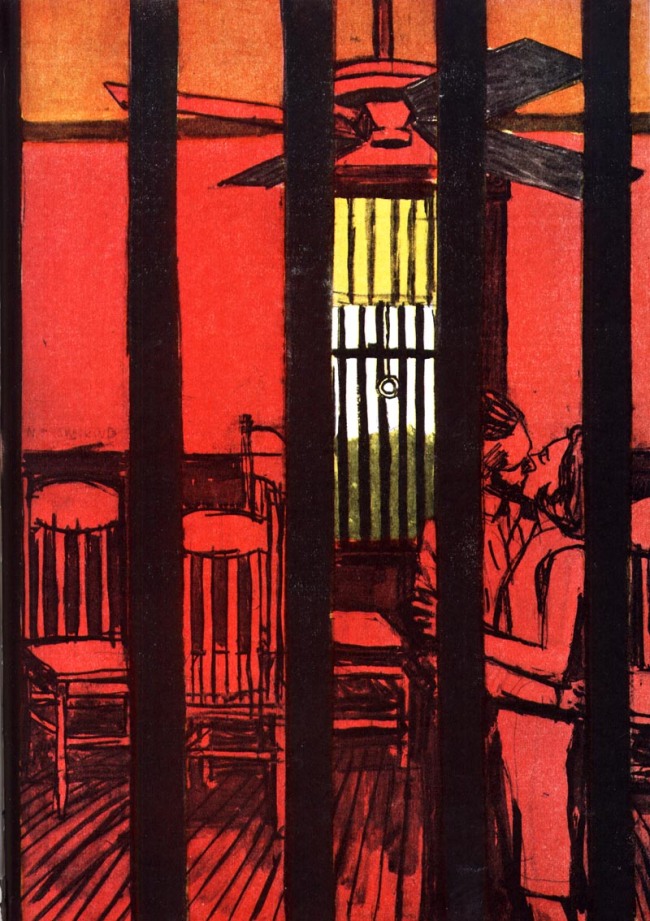

An Illustration for a ‘Cosmopolitan’ editorial.

An Illustration for a ‘Cosmopolitan’ editorial.

Generally, Weaver tended to lend his hand to publications with a primarily male audience, such as ‘Esquire’ or ‘Sports Illustrated’ – not entirely surprising considering the blunt masculinity of his style, which strays from the image of femininity conjured by the stereotypical woman of the 50s. However, I have included above an illustration from a ‘Cosmopolitan’ editorial, showcasing the aforementioned robust draftsmanship of Weaver. What I particularly like about this image is the addition of colour that makes an undeniable impact but does not detract or distract in anyway from the drawing. I also love the chosen perspective and composition, with the view really having to search for the focus of the image – almost as if we are in the shoes of the peeping Tom, trying to capture a glance of this couple stealing a kiss.

From his first job with ‘Town & Country’ in the mid-fifties, Weaver led an exciting 30-year career working from nearly every popular publication of the day: ‘Esquire’, ‘Sports Illustrated’, ‘Charm’, ‘TV Guide’, ‘Look’, ‘Playboy’, ‘The New Yorker’, ‘Seventeen’, ‘Life’, ‘Fortune’. Seeing his work in print never lost it’s excitement to Weaver, some saying the thrill became somewhat of an addiction. In his later years also taught Illustration at the New York’s School of Visual Art, focusing more on this line of his career as magazine illustration falls into decline in favour of photography.

Robert Weaver had an uncanny ability to invite the viewer into the scenario he was documenting, using multiple images to help inform and a haphazard, bold but accurate style that added to the sense of action and immersive nature of his work. Truly these are qualities as an illustrator I can only hope to one day replicate.

REFERENCES:

Zalkus, D. (2008) Melton Prior Institut: Tiger Hunting with the Shah. A Golden Era of Visual Journalism

http://meltonpriorinstitut.org/pages/textarchive.php5?view=text&ID=172&language=English

Smith, R. (1994) New York Times Obituaries

(1990) Art Directors Club, Hall of Fame

http://www.adcglobal.org/archive/hof/1990/?id=429

Heller, S. (2003) Illustrator’s Partnership: The End of Illustration?

http://www.illustratorspartnership.org/01_topics/article.php?searchterm=00073

(2013) Treasures and Musings @ Modern Graphic History Library

http://wulibraries.typepad.com/mghlnews/2013/07/happy-birthday-robert-weaver.html

(2012) Illustrated Love Affair

http://illustratedloveaffair.blogspot.co.uk/

Macmillan, N. (2010) Postwar American Visual Culture: The Work of Robert Weaver

http://americanculture.wustl.edu/dowd/f20_4354/macmillan/macmillan/Home.html

Mullen, C.Dr. (2012) Fortune: Robert Weaver – The Crane Co.

http://www.fulltable.com/vts/f/fortune/ills/weaver/b.htm